Stacey Rolland

There are complex interactions between class, race, gender, and sexual orientation in the ways privacy is thought about and by whom it is allowed to be exercised. We must raise questions of how to better equalize privacy among all Americans.

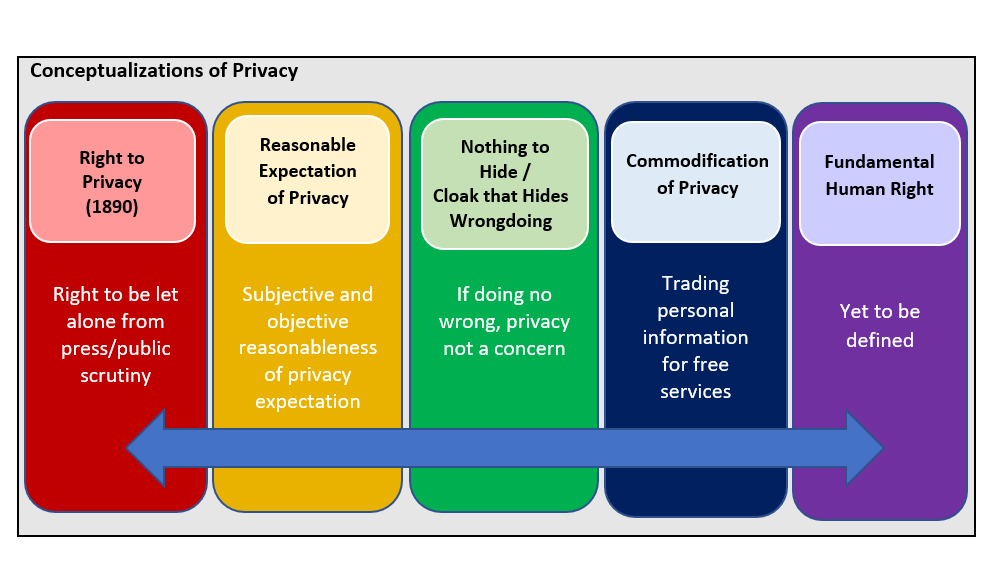

Privacy is an ungrounded concept for most Americans. Depending on the context of who, what, where and why, privacy can mean very different things. Conceptualizations of privacy include:

The Right to Privacy: Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis in their seminal 1890 work The Right to Privacy conceptualized privacy as the right to be let alone, based on the confidentiality Americans deserve from public scrutiny (in their case, the tabloid press).

Reasonable Expectation: In the 1960s, the Supreme Court decision in Katz v. United States formulated the reasonable expectation of privacy. This two-part legal test weighs government imposition upon a citizen’s privacy against the individual’s subjective expectation of privacy and the objective reasonableness of that expectation.

Nothing to Hide: Daniel Solove eloquently discussed in 2011 that debates about privacy and surveillance have centered around the “nothing to hide” argument, whereby only citizens who are engaged in aberrant behavior would be upset by the collection of private information. We can often see within “nothing to hide” the belief that privacy acts as a cloak to hide wrongdoing.

Commodification: Americans also have weighed privacy against consumerism, whereby they commodify their privacy by disclosing personal information to private companies in exchange for free tech services like gaming apps, social media, and electronic communication.

Fundamental Human Right: Today, we hear growing calls for privacy to be determined a fundamental human right. What exactly that means and how it would apply in practice will need to be exhaustively debated.

The different conceptualizations of privacy are never mutually exclusive; they can overlap within a single system, depending on the context and the data subjects involved. When we look more closely at these concepts in practice (briefly discussed below), we must ask how a fundamental right would be justly exercised justly within our current systems.

Privacy as Reasonable Expectation / Privacy as Cloak

When privacy is determined via a balancing test, it matters whose interests are being considered. Vulnerable populations tend to fare more poorly in balancing tests against government interests. Scholars such as Khiara Bridges (in The Poverty of Privacy Rights) and Michele Gilman provide thorough discussions of the right to privacy not fully extending to low-income women of color. The conceptualization of privacy within the system they analyze, the government safety net, is the notion that the use and potential abuse of government resources outweighs the expectation of privacy for recipients of social services. In fact, underlying this balancing test is the “nothing to hide” argument at its most basic level – an assumption of wrongdoing until proven otherwise via a loss of privacy, targeted directly at vulnerable citizens. As Gilman discusses in The Class Differential in Privacy Law,

“fraud prevention is the usual justification underlying welfare surveillance…studies suggest welfare fraud is no more rampant in welfare than in other government programs, which are not subject to the same withering scrutiny.

…there is tension between seeking government assistance and simultaneously demanding privacy from the state. Yet wealthier Americans would recoil in horror if the government put them through similar scrutiny as a condition of receiving government subsidies, such as tax deductions for mortgages and retirement plans, and childcare credits.”

Context (low-income services) and subject (class, gender) influence both the subjective and objective reasonableness of an individual’s expectation of privacy. Our society blends a judgment of reasonableness with the suspicion that privacy can be a cloak to hide fraud. We must consider how a fundamental human right to privacy intersects these systems. If the answer is it would not intersect (say, because the fundamental human right to privacy would only apply in the context of digital privacy), we must probe the fairness of why.

Commodification of Privacy / Nothing to Hide

For many years, Americans have exercised an attitude that they had nothing to hide and, therefore, their data had little value to them. They freely disclose to myriad companies across the globe all sorts of personal information in exchange for low-cost entertainment, social media, and communication tools. However, Americans are becoming more aware of and concerned about the unscrupulous and unchecked uses of their personal data by companies. Unfortunately, these systems have become increasingly complex and protecting their personal data from misuse, monitoring their personal data across hundreds of platforms, or exercising informed consent is cumbersome and time-intensive.

In lieu of regulation that would put guardrails and protections around the disclosure and use of personal data in the U.S., private companies are springing up to provide privacy to consumers as a paid service. A market is developing in which an individual can pay for the service of having private data protected. This introduces a slippery slope whereby outrage is quelled for those Americans with the means to pay for privacy (and political pressure for legal protections are subsequently dissolved), while the data of underrepresented and vulnerable populations, unable or unwilling to pay for such privacy services, continues to be unprotected and commodified with little benefit to them.

The Right to Privacy ≠ Privacy as a Fundamental Human Right

If we are to define a new privacy regime atop the Warren/Brandeis conceptualization of privacy as a right, we must ensure it is not enforceable only for those with the means to exercise that right. As Gilman notes, “the limits of the common law for securing privacy for the poor can be traced to its roots. The right to be left alone was conceived to protect society’s elites (such as Warren and Brandeis) from the glare of public scrutiny.” We must consider the assumptions we impose on the right to privacy and probe the ways the right to privacy has historically been inconsistently applied based on context. These questions must be asked before the right to privacy is used as a foundation upon which we define privacy as a fundamental human right.

Can a Fundamental Human Right to Privacy be Context- and Subject-Specific?

As America debates a fundamental human right to privacy, there will be conflicts between that right and the legal exercise of the reasonable expectation of privacy. It will be difficult for Americans to culturally let go of suspicions that vulnerable populations are hiding fraud and abuse (while remaining relatively tolerant of large-scale fraud and abuse by more powerful entities). One can imagine scenarios in which citizens have a reasonable expectation privacy in some systems and a fundamental human right to privacy in other systems. Privacy would be recognized as a fundamental human right in increasingly narrow contexts – contexts that favor more empowered citizens. For example, we could see privacy framed as a fundamental human right in data storage and data flows but not in data collection and use.

If Americans begin to follow countries like India in debating whether we have a fundamental human right to privacy, we should pay special attention to where the concept of privacy is still limited by the suspicion of wrongdoing. We must challenge our current assumptions about how privacy is exercised in America and ask whether new concepts of privacy recreate or further codify injustices.

As we talk about the future of data privacy in tech, let us ensure the right to privacy is not endowed only to those with power or that a balance in the reasonable expectation of privacy does not weigh against the most vulnerable. We must raise questions of how to better equalize privacy among all Americans.